- Home

- Ray Winstone

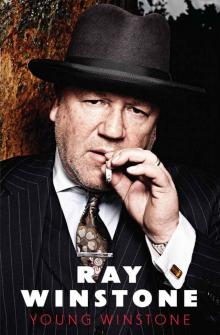

Young Winstone

Young Winstone Read online

YOUNG

WINSTONE

RAY WINSTONE

AND BEN THOMPSON

CANONGATE

Edinburgh·London

Published in Great Britain in 2014 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

www.canongate.tv

This digital edition first published in 2014 by Canongate Books

Copyright © Ray Winstone, 2014

Map copyright © Jamie Whyte, 2014

For picture credits please see p. 251

The moral right of the author has been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

eISBN 978 1 78211 244 0

CONTENTS

Introduction

Map of Ray Winstone’s London

1.Hackney Hospital

2.Caistor Park Road, Plaistow

3.Portway School

4.The Odeon, East Ham

5.The New Lansdowne Club

6.The Cage, Spitalfields Market

7.Ronan Point

8.Raymond’s Tailors, Lower Clapton

9.The Repton Boxing Club

10.Chrisp Street Market, Poplar

11.The Boleyn Ground, Upton Park

12.Victoria Park Lido

13.The Theatre Royal, Stratford East

14.York Hall

15.The Prospect of Whitby, Wapping

16.Nashville’s, Whitechapel

17.Benjy’s Nightclub, Mile End

18.The 277 Bus up Burdett Road

19.Gatsby House

20.The Alexandra Tavern

21.The Tate & Lyle Sugar Factory, Silvertown

22.Hackney Marshes

23.The Corner of Well Street and Mare Street

24.Trossachs, Barking Road

25.The Apollo Steakhouse, Stratford

Picture credits

List of Illustration

Now and then – outside 82 Caistor Park Road in 2014 and as a bouncing baby 57 years before.

My mum with Nanny Rich and the first of her three husbands.

My mum and dad together before Laura and I came along.

Me posing on a blanket like a dog at Crufts.

At another wedding with my cousin Charlie-boy (I’m in the middle, he’s on my right). Not sure who the hatless kid was . . .

Cowboy-style this time in hat terms – with Laura in Nanny Rich’s garden.

Early morning – the Cage with the sun rising in the east behind Christ Church, Spitalfields.

Old Spitalfields Market as it was – good luck finding a sack of King Edwards in there these days.

My dad looking suave on the market.

Spitalfields life before the clean-up, with The Cage, A. Mays and Christ Church in the background.

West Ham bringing home the 1964 FA Cup on their luxury single-decker. All four of the Winstones are in that crowd somewhere.

Repton boys at the London Feds . . . (I’m the one bang in the middle).

With my dad after beating David Heyland (the tall one on the left) who was Essex champ. Although I won, I gave David the bigger trophy – winning was enough for me, and he was a nice kid.

Ready to rumble.

In The Sweeney in 1975, shortly before making my unauthorised escape.

Me in Minder – with George Cole on the right and my fellow Corona old-boy Dennis Waterman between us.

Shadow-boxing with my mate Tony London on the beach at Torquay – Elaine made the right choice.

They called Esther Williams ‘A Goddess when wet’. . .

In Quadrophenia with my leathers and my Liberace haircut.

On honeymoon in the Canary Islands with Elaine and a camel.

We got straight off the plane home and went to the premiere of Scum – note the suitcases and my Quadrophenia badge.

The concluding riot in Scum – no need for Phil Daniels to help me out here. I was the Daddy by this time . . .

Luckily make-up doesn’t sting like a real shiner.

My dad at the bar in Church Street, Enfield – no sign of the Bobby Moore World Cup ice bucket for some reason.

‘Black Magic, Raymond?’ – ‘Don’t mind if I do’.

This is the outfit I wore on that plane trip to Cannes with Alan Clarke – not sure if the ‘foot up’ thing is quite working for me, though.

At the Edinburgh Film Festival with Scum in 1979.

In Canada in 1980 filming Ladies And Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains.

a) With Paul Simonon

b) A beery leer

c) With Steve Jones

d) Elaine offers me a lesson in microphone technique

e) Onstage as lead singer of ‘The Looters’

f ) Elaine is the meat in a Laura Dern/Marin Kanter sandwich

g) Paul Cook shows how a Sex Pistol occupies a chair.

Me with Alex Steene, John Conteh and Perry Fenwick, who plays Billy Mitchell in EastEnders. He’s a great mate of mine who comes from my manor. Well, close enough . . . Canning Town/Custom House.

Even Will Scarlet needs a fag break.

The face that launched a thousand arrows . . .

Lois with me, mum and Toffy, and then getting christened with me and Elaine.

Matthew McConaughey struggles not to look intimidated by my manly physique.

INTRODUCTION

It’s early 2007 and I’m standing on a ship off the coast of northeastern Australia. We’re moored right by Lizard Island, named by my fellow Londoner and Great Briton Captain Cook, and I’m making this film called Fool’s Gold starring Matthew McConaughey, Kate Hudson and my old mate Donald Sutherland, who is a blinding geezer.

Donald is playing an Englishman and I’m playing a Yank, but in hindsight we should’ve swapped roles because I was fucking diabolical in that film – I should’ve got nicked for impersonating an actor. Anyway, I digress . . . a big word for me – seven letters.

So there’s a bit of a buzz going on with a few people running about on deck, and all of a sudden we’re summoned downstairs to this big room with a telly in it. This is the whole fucking crew by the way, with me and Donald hiding at the back like two naughty schoolboys. Then somebody announces it’s the ‘Most Beautiful Man in the World’ Awards.

Well, obviously me and the Don think we might be in the running here, but hold up, the next announcement tells us that our very own Matthew McConaughey is one of the nominees and he’s up against that other alright-looking geezer, George Clooney. Anyway, the show begins and Matthew is giving it the old ‘Woo! Woo!’ like the Yanks do when they get excited. After about five minutes of this bollocks I wanna be somewhere else – anywhere else. Yeah, I suppose I might be a little bit jealous. I mean, he ain’t a bad-looking fella . . .

As they’re building up to the big moment the television shows this satellite going across the world from east to west. Funny how everything and everyone seems to travel from east to west. Maybe they’re following the sun – wanting to find out where it goes before it comes up the other side again – or maybe they thought it went down a hole. Anyway, this satellite is travelling across Europe and as it’s getting closer to London, I’m thinking, ‘You never know . . .’

Bang! It hits London and with all the lapping up that’s going on I can’t contain myself any more. I shout out, ‘Stop right there, my son! That’s me!’ The Aussies, who have a great sense of humour – well, they’re cockney Irish, ain’t they? Or at least the majority are – are all giggling. But as far as the others are concerned, it goes straight over their heads.

Eventually the satellite gets to America and we’re into Clooney and McConaughey territory. We creep quietly past George and slip loudly into Texa

s, and at this point it’s announced that Matthew is the winner. He goes absolutely potty – like he’s scored the winning goal in the World Cup final and won the Heavyweight Championship of the World in one go.

I’m thinking, ‘Fuck me, what a prat!’

The whole thing just seems a bit embarrassing, but then on reflection I start to think maybe this is the big difference between us – apart from my good looks, of course. Maybe this is what makes Matthew a film star, which he is – at the time of writing he’s just won an Oscar, and deservedly so.

Anyway, once I finally get back up on deck, the whole thing kinda makes me think about where I’ve come from. Looking at Australia, 14,000 miles away from home – literally on the other side of the world – I start thinking about me and my mate Tony Yeates as kids in the East End, and I start thinking about Captain Cook. There’s a plaque on the Mile End Road which marks the start of his journey to Oz. It’s just opposite the place a club called Nashville’s used to be, where me and Tony had a few adventures of our own in the late seventies. We’d often find ourselves gazing unsteadily up at that plaque after we’d had a few on a Friday night – dreaming of travelling the world, the places we might see and the people we might meet. And suddenly standing on that ship in the southern hemisphere, it comes to me: ‘I’ve made that journey. I’ve done what Cook did!’

Alright, he did it on a sailing ship and I did it First Class British Airways, but I’ve done it just the same. I’m not trying to book myself as being on Cook’s level as an explorer, but for someone who comes from where I do, getting to the Great Barrier Reef was still some kind of achievement. That was when the idea of paying my own tribute to the places and the people that made me what I am (I won’t be demanding actual blue plaques: ‘Ray Winstone narrowly escaped a good kicking here’ etc.) started to make me smile. I hope it will do the same for you.

CHAPTER 1

HACKNEY HOSPITAL

When I look back through the history of my family, we’ve done fuck all for this country. I don’t mean that in a bad way. The Winstones weren’t villains. We’ve always been grafters, back and forthing between the workhouse and the public house. But at the time I was born – in Hackney Hospital on 19 February 1957 – the Second World War was still very much on people’s minds. It’s probably a bit of a cliché to say ‘everyone had lost somebody’, but in our family, it wasn’t even true. Maybe it was more the luck of the draw in terms of their ages than anything else, but there was no one you could put your finger on and say they had sacrificed themselves in any way.

Doodlebugs rained down on Hackney – I remember being told about one going straight up Well Street – but none of them hit my nan and granddad’s flat in Shore Place. They had to go in the air-raid shelter round the front a few times, but their three young sons – my dad Ray and his two brothers, Charlie and Kenny – were safely evacuated out towards High Wycombe. The village they were lodged in lost three men on HMS Hood, so that was about as close as the war got to them.

Uncle Kenny, my dad’s younger brother, got a start as a jockey and rode a few winners for Sir Gordon Richards’ stable. I’ve always surmised that he must’ve picked up his way with horses when he was evacuated to the countryside, because there weren’t too many racecourse gallops in the East End. That said, his dad, my granddad, Charles Thomas Winstone, did work as a tic-tac man, passing on the odds for bookmakers at tracks all around Britain, so horse-racing was kind of in Kenny’s blood.

When he got too tall to be a jockey on the flat any more, Kenny became a butcher. I guess that was one way he could carry on working with animals. He ended up with a couple of shops – one in Well Street, and one just round the back of Victoria Park – so he did alright. But before that he’d been a pretty good boxer as well. He boxed for the stable boys, and once fought at the Amateur Boxing Association (ABA) finals against a mate of my dad’s called Terry Spinks, who went on to win a gold medal at the Melbourne Olympics aged only eighteen, and would later be known for raising the alarm as the Black September terrorists approached the Israeli athletes’ quarters when he was coaching the South Korean team at the Munich Olympics in 1972. Apparently he gave old Spinksy a bit of a fright.

This wouldn’t have come as any great surprise in the Winstone household, because boxing was what the men in our family did. My granddad had been drafted into a Scottish regiment and stationed in Edinburgh for a while just to be on their boxing team, and when my dad did his National Service with the Royal Artillery, he spent virtually the whole three years in his tracksuit, boxing out of Shoeburyness. I think Henry Cooper might’ve been doing his stint at around the same time, and the only actual service I ever remember my dad telling me about was helping out after the great flood of 1953, when all those people died on Canvey Island.

He said he’d got really angry because the Salvation Army wouldn’t give him a cup of tea when he didn’t have the money to buy one. From then on if he ever saw someone selling The War Cry, he’d just tell ’em to go away. He had no time for those people whatsoever, to the extent that I even remember asking him about it once as a kid: ‘Surely there must be some good people in the Salvation Army, Dad?’ But he just told me, ‘Nah, son, they wouldn’t give me a cup of tea.’

Hopefully this has given you a bit of an introduction to the kind of men I grew up around. I’m going to have to go back a bit further in time for the women, because I came across a story recently which really answered a lot of questions for me about the way I think, and the way the women in my family live their lives. It all started when the Winstones got turned down by the BBC TV series Who Do You Think You Are?

Now, I like that programme – I get right into it (although I have seen some boring ones) – but the first time they asked, I didn’t really want to do it. I enjoy watching them go through other people’s ancestors’ dirty laundry, but when it came to mine, I just didn’t really want to know. That’s all in the past, and it’s the future you want to be thinking about. They kept coming back to me, though, and in the end I thought, ‘Do you know what? Maybe it would be good to find out a few things.’

I knew I had a great-uncle Frank – my granddad’s brother on my mum’s side – who played centre-forward for West Ham. He was at Reading first, and then he moved to West Ham in 1923, the year they got to their first Wembley final. Maybe if they’d bought him before the big game instead of just after it, they might actually have won. As it happens, they got beat, and my great-uncle Frank was a kind of consolation prize, but still, I thought that might be a good starting point.

Unfortunately, it seems that on the show they stick to the direct bloodline, i.e. parents and children only, so an uncle can’t be the story, or at least that’s what they told me. And after giving due consideration to the mountain of material that their researchers had unearthed, they had come to the conclusion that the various roots and branches of the Winstone family tree were just too fucking boring to make a show out of. They were lovely about it – ‘Sorry, Ray, but there’s nothing in here we can use’ – and I did get the giggles on the phone. That can’t have been an easy call to make: ‘Listen, Fatboy, there’s just nothing interesting about you or your family.’

It’s funny looking back, but I was quite depressed about it for a while – not depressed so I wanted to kill myself, just a bit disappointed and choked up. But then I sat down and went through some of the stuff they’d dug up, and I actually got really enlightened by it.

The one thing that did come out of Who Do You Think You Are? was that both branches of my family had been East Londoners for as far back as they could trace. Right the way back to the 1700s my mum’s side came from Manor Park/East Ham and my dad’s from Hoxton and the borders of the City.

OK, my family never changed the world. They never invented penicillin or found the Northwest Passage or won a VC at the Siege of Mafeking. They were basically just people who sometimes fell on hard times and ended up in the poorhouse for a couple of weeks – or longer. But there was one extraordina

ry thing about them, as there is about any family that’s still around today, and this was that they survived. On top of that, it turned out we did have one story worth telling after all, because some time afterwards the same TV company came back to me and said they were making another show that they did want me to be a part of. The subject? There’s a thick ear for anyone who’s guessed it: asylums.

The researchers had discovered that my great-great-grandmother (on my dad’s side) was originally married to a Merchant Navy man called James Stratton, who ended up in the old Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum at Friern Barnet. That was somewhere I’d end up too a century and a bit later, albeit for slightly different reasons – I was shooting the movie version of Scum – but poor old seaman Stratton had got syphilis.

I didn’t find out until we were researching the programme – they like the historians and other experts to break the news to you as you’re going along, so they can catch you looking surprised – just how rife syphilis was in Victorian London. Even before that, going back to Hogarth’s time in the eighteenth century, all those wigs they were wearing in his paintings weren’t just fashion accessories, they were there to cover the fucking scars.

One strange thing that happened was that at one point it actually became fashionable to be syphilitic, so people would wear false noses and ears to make it look like they had it when they didn’t. Wearing a false nose to show you were a proper geezer – how nutty was that? No crazier than covering yourself in tattoos or having plastic surgery you don’t medically need, I suppose.

As far as the unfortunate Mr Stratton was concerned, they thought he’d probably picked the syphilis up in the Navy, before he was married, but then he might have had a dabble again, because the sixth of his eight children was born with it too. Either way, he died a terrible death, leaving my great-great-grandmother alone with all those kids, and no real means of support – visible or invisible.

At this point in the story, the odds must’ve been on her drifting into prostitution. That’s certainly what I thought was going to happen. Because all these events were unfolding around Whitechapel, and the name she went by at the time, Hannah Stratton, had a familiar ring to it – like Mary Kelly or one of those other tragic victims – in my head we were heading towards Jack the Ripper territory. Obviously the programme-makers don’t tell you what’s going to happen because they want you to cry. In fact, they want that so badly they’re practically standing behind the camera with a big bowl of freshly chopped onions.

Young Winstone

Young Winstone